Valencia in Memory

Dades bàsiques

City Council building

SJD Barcelona Children's Hospital

Valencia in Memory is a project of the Department of Heritage and Cultural Resources that recovers for the public space of our city buildings or monuments that had an important role (political, cultural and everyday) during the Civil War, and pays special attention to the year in which Valencia was capital of the Republic (November 1936-October 1937).

A series of milestones (concrete monoliths) give us the most outstanding information, illustrated with historical images, and expandable in a web version, easily accessible thanks to QR codes.

By making these buildings “visible” again, a part of our heritage is recovered for citizens during those important and difficult years. This not only complements the information already available for other periods of the history of Valencia, but also contributes to rescuing important references of our democratic culture.

16 “monoliths” have been placed in the area of public roads, which refer to 16 buildings or groups that have been highlighted for their relevance and that can be followed with a map where all of them are located.

The marked places are the following:

When Valencia was capital of the Second Spanish Republic (1936-1937), this building in the then Plaza de Emilio Castelar housed the official headquarters of the Republican Courts. In May 1937 it suffered serious damage as a result of one of the more than 400 Francoist bombings of the city during the Civil War (1936-1939). Two months later it hosted the II International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture. In the basement there is an air-raid shelter with capacity for more than 700 people.

When Valencia was capital of the Second Spanish Republic (1936-1937), this building in the then Plaza de Emilio Castelar housed the official headquarters of the Republican Courts. In May 1937 it suffered serious damage as a result of one of the more than 400 Francoist bombings of the city during the Civil War (1936-1939). Two months later it hosted the II International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture. In the basement there is an air-raid shelter with capacity for more than 700 people.

Location: Town Hall Square, 1

Of late medieval origin (late fourteenth century), the Torres de Serranos played a key role during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). During the first weeks they hosted one of the 26 emergency health posts that the defenders of republican democracy organized in Valencia in response to the violence caused by the coup d’état led by Franco and other generals in July 1936. Later, they functioned as a repository-refuge for the historical-artistic heritage.

Of late medieval origin (late fourteenth century), the Torres de Serranos played a key role during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). During the first weeks they hosted one of the 26 emergency health posts that the defenders of republican democracy organized in Valencia in response to the violence caused by the coup d’état led by Franco and other generals in July 1936. Later, they functioned as a repository-refuge for the historical-artistic heritage.

First, of works of local art, mainly religious, confiscated by the Republican City Council with the intention of avoiding new destructions such as those caused on July 20 and 21 by the spontaneous attacks on churches in the city in reaction to the uprising. Later, they also housed the most valuable part of Spain’s historical-artistic heritage, transferred by truck from Madrid with the intention of protecting it from Francoist bombings. Bombings that would affect, among others, the Prado Museum, from which many of the works preserved here came, such as Goya’s Two of May, Velázquez’s Christ Crucified or Titian’s Venus.

This risky transport operation – at night and under military protection – began on November 10, 1936, just three days after the transfer of the government and the capital of the Republic to Valencia and, in fact, also responded to the latter’s desire to maintain direct control over the “national” heritage as a hallmark that reinforced it as the only legitimate government of the nation.

Chosen for its architectural characteristics, this old gateway to the city was adapted, reinforcing its structure to provide greater protection against bombing, or installing, among other interventions, electrical devices to prevent moisture from deteriorating the paintings.

This success was evident in the perfect conservation of paintings, tapestries and books, verified in situ by international experts such as Frederic Kenyon, former director of the British Museum, who visited Valencia in the summer of 1937. Between March and April 1938, as Franco’s troops advanced through the regions of Castellón, these works were moved to Catalonia and finally crossed its borders thanks to an international agreement. However, until the end of the war, the Torres de Serranos continued to fulfil the same function, going on to preserve the artistic treasures of Segorbe, Castellón and other towns threatened by the rebels helped in their advance by troops from fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

Location: Plaça dels Furs, s/n

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) was the first war in Europe in which population centers were bombed from the air in high numbers and indiscriminately. Between January 1937 and the end of the war, in March 1939, it is estimated that the city of Valencia suffered more than 400 raids by sea and air, that is, an average of one every two days during the last two years of the conflict. Often in charge of the aviation and navy of fascist Italy, allied to the Franco side, the bombings caused more than 800 deaths, almost 3,000 injuries and more than 900 buildings destroyed.

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) was the first war in Europe in which population centers were bombed from the air in high numbers and indiscriminately. Between January 1937 and the end of the war, in March 1939, it is estimated that the city of Valencia suffered more than 400 raids by sea and air, that is, an average of one every two days during the last two years of the conflict. Often in charge of the aviation and navy of fascist Italy, allied to the Franco side, the bombings caused more than 800 deaths, almost 3,000 injuries and more than 900 buildings destroyed.

The Passive Defense Board had the mission of organizing the response to increasingly frequent bombings. One of the main measures was the construction or habilitation of more than 300 air-raid shelters, of public or private ownership. Built underground on a available plot at the confluence of Dalt and Ripalda streets, this had capacity for about 600 people in its 362m2. At street level only the ‘aerial part’ is visible, above ground level, which included the entrances and the levels of protection that had to cushion a large part of the denotation in case of a bomb hit. Its location is still easily identifiable by the letters REFUGIO, placed on its façade in Art Deco style, a typography characteristic of the time. This is one of the few shelters in the city that still retain their original signage.

Two arrows pointing in opposite directions marked the entrances, so that the population of the city could find them without difficulty once the anti-aircraft sirens began to sound. The entrances were usually built as far away from each other as possible, in order to make it difficult to destroy them simultaneously in the event of an eventual impact. Likewise, the access corridors that gave access to the interior of the shelters used to have an arrangement ‘on the elbow’, that is, at right angles, so that, in case a bomb exploded at the door, shrapnel did not affect the refugee civilians inside. At the end of the bombing, alarms rang again to indicate to the population that the danger had passed.

Location: Carrer de Dalt, 33, corner of Ripalda street

When Valencia was capital of the Second Spanish Republic (1936-1937), this nineteenth-century palace – located in what was then Plaza de los Trabajadores – became the headquarters of the Ministry of Health and Social Assistance. It was a newly created ministry, unprecedented in the Spanish governmental structure, bringing together powers until then assigned mainly to the Ministries of Governance and Labour. With the arrival of the Government, its first headquarters were in the Palace of Montenegro (which still exists at Calle Sorní, nº 3, very close to the Colón metro stop), which housed the Health Committee of the Provincial Department of Health.

When Valencia was capital of the Second Spanish Republic (1936-1937), this nineteenth-century palace – located in what was then Plaza de los Trabajadores – became the headquarters of the Ministry of Health and Social Assistance. It was a newly created ministry, unprecedented in the Spanish governmental structure, bringing together powers until then assigned mainly to the Ministries of Governance and Labour. With the arrival of the Government, its first headquarters were in the Palace of Montenegro (which still exists at Calle Sorní, nº 3, very close to the Colón metro stop), which housed the Health Committee of the Provincial Department of Health.

At her head was the Catalan anarchist Federica Montseny i Mañé (1905-1994), the first woman minister in the history of Spain and one of the first in Europe. Although his appointment was not without controversy, the press of the time was quick to highlight its meaning. According to the graphic magazine Estampa, it was:

“the entry of a woman into the central office of a Ministry, an event that perfectly delimits the two aspects: the new, that of ample possibilities for all that has aptitude for things, and the old, that which we ourselves discover by highlighting this same appointment of minister for a woman, something that would have seemed so natural and spontaneous if we did not all have the intelligence so attached to that web of old prejudices that He’s always surrounded us.”

Location: Plaça de l’Arquebisbe, 3

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), next to this then Plaza de Vinatea (baptized in memory of Francisco de Vinatea, jury of the city in the fourteenth century), the Micalet housed the nerve center of the Special Defense Against Aircraft. The DECA coordinated the local passive defense system and warned of the arrival of bombers, usually belonging to the Aviazione Legionaria. Based in Mallorca, the arrival by sea made it impossible to detect them well in advance, despite the use of phonoreceptors to hear the noise of the engines beforehand.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), next to this then Plaza de Vinatea (baptized in memory of Francisco de Vinatea, jury of the city in the fourteenth century), the Micalet housed the nerve center of the Special Defense Against Aircraft. The DECA coordinated the local passive defense system and warned of the arrival of bombers, usually belonging to the Aviazione Legionaria. Based in Mallorca, the arrival by sea made it impossible to detect them well in advance, despite the use of phonoreceptors to hear the noise of the engines beforehand.

The observation outposts distributed between the coast and Ciutat Vella therefore had a minimum response time to notify the observation centre in El Micalet, which ordered the sirens to sound and open fire on the anti-aircraft batteries. It was an insufficient and obsolete system to deal with modern air warfare. In fact, we have no record of any attacking aircraft being shot down over Valencia and the main task of the Passive Defence Board (created in April 1937) was to minimise the loss of life among the civilian population in the event of an attack.

Hearing the sirens (three to five minutes long), people ran to shelters, such as this one, built in 1938 on the former site of the Batlia (or City House); However, its size and capacity are unknown. After the threat, the sirens sounded again for two minutes to warn the population that they could return to the streets. To date, only one of the city’s twenty-five mermaids remains, on Calle Martínez Aloy.

Since the return of democracy, the Palau de la Generalitat has been the seat of the Presidency of the Council, the Valencian Government. Built largely in the fifteenth century and declared an Asset of Cultural Interest (BIC) already in 1931, the building housed during the months after the coup d’état of 1936 the Popular Executive Committee (CEP), true alternative power and the only political government body for the Valencian rearguard. It had representatives of all the political and trade union forces that supported the cause of the Republic: two representatives from the UGT and two from the CNT, one from the FAI and one from each.

Location: Carrer de Cavallers

The Borgia Palace, the current headquarters of the Valencian Courts, was built by the Borgia family, Dukes of Gandia, between the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. During the last Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), with the transfer of the government and the capital of the Republic to Valencia, the building housed the headquarters of the Presidency of the Government, as well as the Ministry of War. Here took place the first council of ministers held in Valencia the day after the transfer, on November 7, 1936, which served, among other things, to make the important decision of how to communicate to public opinion the controversial transfer from Madrid. In fact, it was necessary to make it clear that this was not an abandonment, nor a sign of weakness in the face of Franco’s troops’ advance, but a strategic decision to make the management of the cabinet more effective: “to articulate the efforts of the whole antifascist Spain at the service of total victory and the liberation of Madrid itself”, as indicated by an official note.

The Borgia Palace, the current headquarters of the Valencian Courts, was built by the Borgia family, Dukes of Gandia, between the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. During the last Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), with the transfer of the government and the capital of the Republic to Valencia, the building housed the headquarters of the Presidency of the Government, as well as the Ministry of War. Here took place the first council of ministers held in Valencia the day after the transfer, on November 7, 1936, which served, among other things, to make the important decision of how to communicate to public opinion the controversial transfer from Madrid. In fact, it was necessary to make it clear that this was not an abandonment, nor a sign of weakness in the face of Franco’s troops’ advance, but a strategic decision to make the management of the cabinet more effective: “to articulate the efforts of the whole antifascist Spain at the service of total victory and the liberation of Madrid itself”, as indicated by an official note.

During the year of the Borgias, the official receptions of the President of the Government were held during the year of the capital. From his windows, the man in office at the time, the socialist Francisco Largo Caballero, staged an important demonstration of support for the democratic government held on February 14, 1937, shortly after the fall of Malaga to rebels aided by Italian fascists, which resulted in massive repression. In the basement of the building there is a shelter that, today, is used as a storage for publications. During the dictatorship (1939-1975) it served as Franco’s residence on his visits to Valencia. In 1973 the building was acquired by the Ministry of the Interior and during the transition to democracy it became the headquarters of the Presidency and various ministries of the Council of the Valencian Country, that is, the pre-autonomous government. Finally, in 1983 the Borgia Palace was ceded by the Ministry to house the headquarters of the Valencian Parliament, the legislative power of the Valencian people; in 1994 the various adaptation works carried out at the Palau were completed to adapt it to its current function.

Location: Plaça de Sant Llorenç, 3

The building of the current Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia was built between the late seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century as the San Pio V School for the training of priests. In 1835 it passed into the hands of the army, which set up a military hospital.

The building of the current Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia was built between the late seventeenth century and the first half of the eighteenth century as the San Pio V School for the training of priests. In 1835 it passed into the hands of the army, which set up a military hospital.

During the last Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), in a context of health emergency, the San Pio V Military Hospital became the main center of a network that came to consist of fifteen Valencian military hospitals. With 701 beds distributed in 35 rooms, operating rooms, polyclinics and infectious diseases pavilion, it was essential in the care of wounded soldiers at the front. Particularly relevant was his role during 1938, in relation to the battles in Teruel and Castellón, which resulted in the defeat of the democratic forces and with a large number of wounded: 904 only in the case of the former. Along with the work of doctors belonging to the Military Health Corps, it is necessary to recognize the work of the large female personnel, essential in the care of the wounded and sick; The generally voluntary nature of these women’s contributions often revealed their commitment to the anti-fascist cause. Since 1946 the building has housed the Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia, one of the three most important art galleries in Spain.

The monastery of the Trinity, whose original building dates from the thirteenth century, was inhabited since the fifteenth century by religious Poor Clares. Abandoned due to fears of uncontrolled attacks by opponents of the military uprising during the first weeks of the civil war, the building was occupied and used for military purposes, as happened with many other religious buildings. Thus, it served as barracks for the 10th regiment of the Army of the Republic and for the International Brigades, composed of foreign volunteers in favor of republican democracy. Not surprisingly, it had the active support of well-known personalities such as Willy Brandt, Josip Broz Tito, Ernest Hemingway or George Orwell. In what had been an orchard of the convent, an air-raid shelter was built, which is currently in good condition and preserves the benches, part of the ventilation system and the auxiliary buildings. After suffering significant damage and transformations during the war, with Franco’s victory the monastery was once again occupied by the nuns and is now uninhabited.

Location: Streets of Sant Pius V, 9, and Trinidad, 13

When Valencia was capital of the Second Spanish Republic (1936-1937), the building of the Caja de Ahorros y Monte de Piedad housed the newly created Ministry of Propaganda. It was accessed through the official entrance, to the then Maria Carbonell Street, named before the war in memory of the Valencian María Carbonell Sánchez (1852-1926). With Catholic convictions and close to the conservative sector of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, she was a teacher at the Normal Female School of Valencia and author of a profuse work. Much loved in the city, she became one of the most remembered figures of Valencian pedagogy.

The Ministry of Propaganda had been created on November 4, 1936, three days before the transfer of the Government to Valencia. Here he occupied the then new building designed by the Valencian architect Antonio Gómez Davó, built in the early 1930s. With the journalist from Alicante Carlos Esplà (1895-1971), from the Republican Left, at its head, the mission of the Ministry was to sustain the morale of the population and coordinate the slogans of institutions, parties and unions. In the words of its undersecretary, Federico Martínez Miñana, in the graphic magazine Crónica, it was necessary to make “propaganda of the whole Government and everything that is worth the parties and trade unions abroad”, recognizing its political plurality of forces, but prioritizing common elements in the institutional message of the Republic. In addition, in order to present the cause of democracy at the important international level, it was necessary to reach “the five parts of the world to disseminate and signal the just cause that the Republic of Spain defends”.

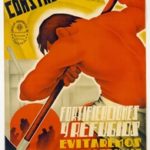

In order to accomplish its mission, the Ministry was divided organically into different departments: Information for the Foreign Press; of Editions and Publications; Film and Radio; a Photographic Service and a sound file or ‘Disco’. Especially during its capital, the Ministry was one of the political actors that contributed to the intense politicization of Valencian society, filling with posters, banners and murals, walls and facades of official buildings (ministries, City Council and institutions, such as the Popular Athenaeum) and, in general, the streets of the city center.

The basement of the building was adapted to house one of the largest air-raid shelters in Valencia, with the capacity to protect – as reported by the anarchist newspaper Fragua Social – about 2,800 people from the more than 400 air raids suffered by the city until the end of the war.

Location: General Tovar Street, 3

Side façade of the Ministry of Propaganda, with its official signage on the balcony and numerous political posters on its lower walls, at street level. Photograph: Archivo General de la Administración (Alcalá de Henares, Madrid).

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Valencia suffered more than 400 air and naval attacks, often by the navy and aviation of fascist Italy, allied – like Nazi Germany – to the Franco side.

In the interwar period, fears had spread throughout Europe that, as a result of the development of military aviation, in the event of a new war, cities would become great targets, totally unprotected as they were against the new threat from the sky. This fear became a reality for the first time systematically and indiscriminately during the Spanish Civil War.

Although prohibited by the Hague Convention since 1907, bombing raids against defenseless civilian populations then affected small, medium, and large cities. Thus, the German Luftwaffe and the Italian Aviazione Legionaria converted, among many others, Durango, Gernika, Xativa, Castellón, Madrid or Barcelona into a testing ground where they could harass what they would shortly afterwards launch on a much larger scale over Warsaw, Rotterdam, London or Belgrade.

In the city of Valencia, which became a first-rate civilian target when it was designated capital of the Republic in November 1936, the first bombings came two months later. Bombs dropped from the sky and coast until the last days of the war, in March 1939, killed more than 800 civilians and wounded more than 2,800, destroying more than 900 buildings.

To protect the civilian population, in 1937 the Passive Defence Board built here – very close to an important political centre, such as the then Plaça de la Senyera (today, in Tetuan) – a medium-capacity air-raid shelter. In its 267 m2 it could accommodate about 380 people, protected by a reinforced concrete structure that could withstand the impact of bombs of up to 200-250 kg.

Located in an alley, poor visibility recommended placing a second sign on the corner of Calle Espasa and Plaza with the letters REFUGIO in Art Deco style, to indicate its location so that, in case of bombing, the population could locate it quickly. While this second sign is preserved, from the original on the façade of the refuge on one of the two doors, at this moment you can hardly even guess the footprint left by the letters already disappeared.

Many of the city’s shelters, especially those newly built with a visible aerial part (Plaça del Carme, Generalitat,..), were not destroyed until the end of the Second World War, when it became clear that Spain would not go to war alongside Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. The shelter on Sword Street, however, was not destroyed: abandoned, it also survived the post-World War period, and gradually deteriorated for decades. At present, its two entrances are closed but inside it still retains the running benches to be able to pass the (often) hours of tense waiting, as well as remains of the machinery and ventilation pipes. As for its heritage protection, the refuge is listed as an Asset of Local Relevance (BRL) for its historical, cultural and archaeological value.

Location: Espada Street, 22

Propaganda poster about the construction of shelters. Manuel Gallur, 1938. Photograph: Historical Library of the University of Valencia.

In the Plaza de Tetuán, the fate of the coup d’état against the republican democracy that gave rise to the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) was largely elucidated.

On July 18, 1936, the building of the Captaincy General (former Royal Convent of Sant Domènech) housed the General Headquarters of the III Organic Division of the Spanish Army, which included the military detachments of Albacete, Alicante, Castellón, Murcia and Valencia, under the command of Brigadier General Fernando Martínez-Monge Restoy (1874-1963). The control of the Captaincy was a key factor in revolting the garrisons of its jurisdiction, but also, the strategic position of Valencia with respect to Madrid and Barcelona, could influence the final fate of the anti-republican insurrection. In front of the Captaincy, the headquarters of the Derecha Regional Valenciana installed in the neoclassical Palace of the Counts of Cervelló, a historic building of liberal memory where Ferdinand VII repealed the Constitution of Cádiz, of 1812 (the “Pepa”), to restore absolutism.

Armed militants of the Regional Right and the Phalange had gathered in the Palau de Cervelló on 18 July 1936 to support the officers conjured up with the aim of revolting and taking control of the Captaincy, and in the square the first armed confrontation with a car of republican militiamen took place. In the Captaincy, the insurgent officers waited for the final moment to control the power of the military forces but, like other officers, Martínez-Monge decided to remain loyal to the legitimate government. Among other factors, his attitude helped to decide the failure of the anti-republican plot in Valencia and was never forgiven by the coup plotters. At the end of the war in 1939, Martínez-Monge – always loyal to the Republic – went into exile and died in Buenos Aires (Argentina).

Already in the midst of the civil war, the Palau de Cervelló housed the Regional Committee of the Communist Party, which caused the then Plaza de la Senyera to be popularly known as ‘Red Square’. On October 30, 1936, the square was the scene of a serious event: the armed confrontation between communists and anarchist militiamen, due to their differences when it came to organizing the economy, politics and the army. This clash, which preluded the so-called ‘May Events’ of 1937 in Barcelona, ended with the provisional result of more than 20 deaths.

Already in the midst of the civil war, the Palau de Cervelló housed the Regional Committee of the Communist Party, which caused the then Plaza de la Senyera to be popularly known as ‘Red Square’. On October 30, 1936, the square was the scene of a serious event: the armed confrontation between communists and anarchist militiamen, due to their differences when it came to organizing the economy, politics and the army. This clash, which preluded the so-called ‘May Events’ of 1937 in Barcelona, ended with the provisional result of more than 20 deaths.

After having hosted during the nineteenth century, among others, Fernando VII, the Regent Maria Cristina or Isabel II, today the Palau de Cervelló is one of the main cultural spaces of the city, houses the Municipal Historical Archive and houses exhibitions or spaces such as the Ballroom and the Library. At the same time, the interior of the Captaincy General has preserved an important historical-artistic ensemble.

Location: Plaça de Tetuán

Calle de la Paz is the result of one of the most important urban reforms of Valencia in the late nineteenth century, which shaped it as a residential area for the bourgeoisie.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), this modern artery became one of the axes of the political life of the city, particularly during the year in which Valencia held the capital of the Second Republic, between November 1936 and October 1937, as a result of the transfer of the democratic government from Madrid threatened by Franco’s troops supported by Nazi Germany and fascist Italy. Thus, the posters, signs and banners hanging from numerous buildings and premises on Calle de la Paz testified to the notable intensification of political and cultural life in Valencia.

In fact, in mansions and spacious flats abandoned by their wealthy owners who fled due to the fear of republican repression, or confiscated from them, the headquarters of various political and cultural organizations and institutions linked to the defense of the Republic were installed, such as the Ministry of Public Instruction (at number 39 of this road), the Regional Federation of Libertarian Youth of the Levant (nº 40), the Regional Federation of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI) and Popular Culture (nº 23), dedicated to educational tasks.

The headquarters of the Regional Committee of Free Women (nº 29) and the Provincial Committee of Antifascist Women (nº 38) revealed the crucial mobilization of women supporters of the Republic in welfare, propaganda, cultural and educational activities, conceived as part of the war effort.

For its part, the luxurious Palace Hotel (nº 42), renamed the “House of Culture”, became the residence and workplace of numerous intellectuals, artists and scientists transferred from Madrid with the support of the government, who contributed to revitalizing the cultural life of Valencia. Sarcastically called by the Valencians “El Casal dels Sabuts de tots sorta”, its patronage was chaired by the poet Antonio Machado, and it was visited by personalities such as Rafael Alberti, María Teresa León, Luis Cernuda, León Felipe, Octavio Paz, John Dos Passos and André Malraux. In the same street, the cafeteria Ideal Room (nº 19) became a meeting place for republican intellectuals, diplomats, soldiers and foreign correspondents.

However, Carrer de la Pau was also no stranger to the bitterer side of the war: four basements (numbers 14, 22, 25 and 40) were set up as air-raid shelters, with a total capacity for 765 people. On January 26, 1938, a virulent attack by Italian fascist aircraft on civilian targets caused nearly a hundred deaths.

Location: Carrer de la Pau

In 1917 the Compañía de los Caminos de Hierro del Norte de España (included in RENFE when it was nationalized in 1941) inaugurated this railway station designed by Demetrio Ribes, a splendid modernist jewel, popularly known as the North Station.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) this space condensed the effects of the “total war” on the civilian population, but also symbolizes in our present the enormous display of solidarity with millions of evacuees. From the first days of war, tens of thousands of non-combatants (the elderly, women, children) left their homes and headed for Madrid to flee preferentially from the political violence deployed by the rebel army in its advance through Andalusia, Extremadura and Castilla-La Mancha.

In the Spanish capital they began to suffer the planned terror of the bombings of the Nazi-fascist aviation, governments allied to the coup plotters, to later suffer the military siege of the city.

Madrid then organised the evacuation of the elderly, women and children to the still quiet rear areas. In Valencia, the Estación del Norte became the nerve centre of this evacuation, directed and sustained with the support of the example of solidarity deployed by Valencian and state public institutions, trade unions, parties, associations and international aid. At the station, the National Refugee Committee attended to the first food and health needs of evacuees. Subsequently, the evacuated group was distributed to the Valencian provinces, Catalonia and Murcia, with a particular attention to childhood (school colonies).

In Valencia, capital of the Republic (November 1936-October 1937), the National Committee of Refugees was installed (Salvador Seguí street, now Conde de Salvatierra) and its successor, the Central Office for Evacuation and Assistance to Refugees (OCEAR), which established in Valencia one of the two Stage Offices for the Evacuation and Assistance to Refugees.

The Department of Social Assistance of the Provincial Council of Valencia (Plaza de los Derechos del Niño, 2, currently de San Luis Bertran) also maintained its protection centres for evacuees.

Thus, at the end of 1936, the Valencian territory welcomed some 250,000 evacuees and the city of Valencia received the congratulations of the Health Mission of the League of Nations (precursor of the current UN) for its attention to evacuees. The progressive Republican military defeats since early 1937 forced millions of people from Malaga, Asturias, the Basque Country, Aragon and the province of Castellón to evacuate to the Republican rearguard. Thus, the city of Valencia would go from about 320,195 inhabitants in the thirties, to 413,969 in 1939, when the war ended.

Thus, at the end of 1936, the Valencian territory welcomed some 250,000 evacuees and the city of Valencia received the congratulations of the Health Mission of the League of Nations (precursor of the current UN) for its attention to evacuees. The progressive Republican military defeats since early 1937 forced millions of people from Malaga, Asturias, the Basque Country, Aragon and the province of Castellón to evacuate to the Republican rearguard. Thus, the city of Valencia would go from about 320,195 inhabitants in the thirties, to 413,969 in 1939, when the war ended. This constant population increase put pressure on health services, accommodation and food supplies, as well as a challenge to manage this humanitarian crisis. Despite occasional conflicts of coexistence, solidarity managed to limit, especially with children, the devastating consequences of the war.

Currently, the North Station is a Historic-Artistic Monument and Asset of Cultural Interest, as well as one of Adif’s historical stations contemplated in the Spanish Historical Heritage.

Location: Carrer de Xàtiva, 24

The College of Saint Joseph, of the Society of Jesus, was founded in 1870 as a secondary school and is one of the examples of the Catholic mobilization of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in defense of the Church and its postulates. In this case, the initiative was aimed at educating the children of the city’s influential families.

The Company chose this location because it was located on what was then the outskirts of the city, in a healthy and hygienic area. Construction of the building began in June 1879 and was completed in September 1880. Later it underwent successive extensions that involved the construction of the chapel and the assembly hall, as well as the extension of the side wings, initially with only one floor, unlike the rest of the building that had three, until they were equalized to three floors in the 1920s. With this latest extension and the purchase of two plots of land towards the Turia riverbed, in 1922 and 1926, we arrive at the image that the Association had in the thirties.

Shortly after proclaiming the first Spanish democracy, the Second Republic (1931-1939), being owned by the Society of Jesus, this institution was affected by the provisions of article 26 of the 1931 Constitution: dissolution of the Society of Jesus and nationalization of its assets, which would be dedicated to charitable and educational purposes.

For this reason, from 1932, different institutions dedicated mainly to education began to be installed, which was strengthened during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Thus, this complex became an example of the educational action carried out by the Second Spanish Republic, both in times of peace and war.

Thus, near the river, at the end of what was then called Gran Via de Ramón y Cajal de Valencia, the following institutions gathered:

a) The Institute-School: created in Valencia in 1932, it was a characteristic example of the application to a public centre, aimed at mainly – but not only – secondary school students, of the pedagogical and methodological principles of the Free Education Institution.

b) The Workers’ Institute of Valencia: created in November 1936 and inaugurated in January 1937, the abbreviated baccalaureate, approved shortly before, was applied. Lasting two years with two semester courses per year, this abbreviated baccalaureate had as its fundamental objective to facilitate access to the University for the popular and working sectors.

c) The Blasco Ibáñez National Institute of Second Education, the second secondary school in the city after Lluís Vives: created in 1933 and previously located in different places of our Cape and Casal, especially in the surroundings of the Eixample de Ruzafa (streets of Almirall Cadarso and Avenida del 14 de Abril, current Kingdom of Valencia), was installed here at the beginning of 1937.

d) The Luis Bello School Group, the only primary school in the whole group, together with the General and Differential schools of the Institute-School.

e) The Normal School. The training institution for future teachers was moved in 1932 from its original place, the House of Education, located behind the Town Hall, to Archbishop Mayoral Street. During the war, it also housed Normal 1 in Madrid and, when the Workers’ Institute was installed there, it had to move, in March 1937, first to the School of Craftsmen (Avenida del 14 de Abril) and then to Avenida de Mariano Aser (now Paseo de la Alameda).

Franco’s victory meant the disappearance of this educational complex, not only because the property was returned to the Society of Jesus, but also because the institutions it housed were eliminated, such as the Institute-School or the Workers’ Institute, or transferred and modified, such as the Blasco Ibáñez Institute, which was installed again in the street of Almirante Cadarso. now with a new name (San Vicente Ferrer) and with new recipients, it would become the city’s women’s high school.

Location: Gran Via Ferran el Catòlic, 78

After more than a decade under construction, the Valencia Model Prison was inaugurated in June 1903. The newspapers of the time echoed the slowness of its construction and its economic cost, as well as the delay in transferring inmates from other prisons and putting it into operation.

When it was built, the new prison was located two kilometres from the city, on the line of the electrically powered tram that ran along the Valencia-Torrent route. It was the first building in the city built directly for a penitentiary purpose. It consisted of 528 cells spread over four radial galleries; plus 16 for “distinguished” prisoners – for a fee, 10 for “politicians” and an isolated department for young people. In addition, it had an infirmary, laundry, a workshop pavilion, parlours, chapel, six public fountains, machinery for the production of electric lighting or water evacuation system.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), the city of Valencia remained in a republican zone until the end of the war, becoming the capital of the Republic for one year. In this period, the Model Prison continued to house prisoners for common crimes, such as theft, robbery, or homicide. In the context of war, inmates for subsistence-related activities were added: smuggling, hoarding, price alteration and concealment of basic necessities. On the other hand, prisoners accused of supporting the coup d’état against republican democracy and rebels, espionage, defeatism, treason or hostility and disaffection. In fact, trials were held in the courtroom itself in the building itself.

Thus, people suspected of harmony with the coup plotters and acting against the republican government, among others, priests and Falangists – members of the Falange, the Spanish fascist party, were held in the prison galleries. In addition, anarchists from the CNT-FAI trade union and members of the POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification) were also imprisoned there, in the context of tensions between the different tendencies opposed to the revolt. Despite the multiple incarcerations, the conditions of health, habitability and food were not as harsh as they would be in the years after the end of the war. Thus, between October 1936 and March 1939, 14 people died from Valencian municipalities, but also from other provinces.

After the end of the war and the implementation of the Franco dictatorship (1939-1975), the building did not change its penitentiary use. In the most intense moments of the post-war repression, more than 10,000 prisoners were concentrated, far exceeding their capacity. The prisoners, common and political, suffered from overcrowding and poor food, hygiene and sanitary conditions. Under these circumstances, parasites proliferated – bed bugs, lice, fleas; avitaminosis, diarrhea or diseases such as scabies and pneumonia. As a result, between April 1939 and 1943, 193 people died in the Valencia Model Prison.

The Model Prison ceased to be used as a prison in 1991. Shortly afterwards, the well-known film by Luis García Berlanga “Todos a la cárcel” was shot inside and years of abandonment began until its rehabilitation. It currently houses the 9 de Octubre Administrative City.

Location: Calle de la Democracia, 77

The geostrategic and geopolitical situation of Valencia during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), the proximity of the Teruel front and the unfavourable course of the war for the Republican side turned the Valencian cape and casal into a receiving pole for war wounded and the civilian population evacuated from places such as Madrid, Malaga or Asturias. on many occasions sick. Faced with this marked increase in the demand for assistance, the Valencian authorities made a great effort to reorganize the city’s network of health infrastructures.

However, this intense health reorganisation was unable to absorb the high demand for healthcare caused by intense demographic pressure. Thus, from the end of 1936 a progressive collapse of the health infrastructures of the city of Valencia began, a process that became more acute throughout 1937 and culminated in 1938 with the solsida of the healthcare system.

The readaptation of the city’s health system to the new war situation caused by the coup d’état of July 1936 crystallised in two ways. Firstly, the hospitals that existed before the war underwent a marked internal reorganisation in order to increase their healthcare capacity. On the other hand, numerous hospitals were set up in all types of buildings: schools, convents, private clinics, chalets… These were the so-called Blood Hospitals, intended for the care of sick and wounded militiamen and, later, soldiers.

Nazareth Hospital fits into this second group; Indeed, on August 25, 1936, the Nazareth Defense Board informed the People’s Health Committee of the setting up of a blood hospital with a capacity of 30 beds. Housed in the summer house of the Monfort family, a wealthy family from Valencia, the health center was located very close to the emergency sanitary post that had been improvised in the “Español” cinema (number 45 of Calle Mayor). For this reason, the same health personnel attended both facilities. In addition, many neighbors volunteered to collaborate in the auxiliary tasks of the hospital (cleaning, supply, etc.).

On January 12, 1937, the port of Valencia suffered a bombardment by an Italian fascist submarine, and one of the shells hit the hospital, causing some damage and an approximate total of 9 dead and 11 wounded in its surroundings and in the whole of the Maritime Villages. The accident book of the Provincial Hospital recorded at 11:00 pm the arrival of three injured people from Nazareth. Likewise, the press of the time highlighted the attention in the Llevant Relief House to several injured residents of Nazareth in front of the blood hospital.

Location: Calle Mayor de Nazareth, 80

Damage inside the Nazareth Blood Hospital caused by the bombing. Photograph: Biblioteca Nacional de España.

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Valencia became a city receiving war wounded and an evacuated civilian population, often ill. This situation forced the Valencian authorities to reorganize the city’s hospital network. Firstly, the hospitals that existed before the war underwent a marked internal reorganisation with the aim of increasing their healthcare capacity. On the other hand, numerous hospitals were set up in all types of buildings: schools, convents, private clinics, chalets… These were the so-called Blood Hospitals, intended for the care of sick and wounded militiamen, and later, soldiers.

SJD Barcelona Children’s Hospital belongs to the first group of hospitals; indeed, the Hospitaller Order of St. John of God had been established in Valencia in 1887, initially in the Benimaclet neighbourhood. Under the name of Asilo de San Juan de Dios, the aim was to welcome “stunted children, scrofulous children, poor eggs, shelves and counter-hechos”. In 1892 the asylum had moved to an old mansion located very close to the Malvarrosa beach. Following the hygienist criteria of the time, in 1907 the current hospital was designed, and in 1913 it was inaugurated.

Shortly after the military coup of July 1936, the Sant Joan de Déu Hospital was seized and managed by the Communist Party, and received the name of Sanatorio Hospital Popular. Although at first the friars continued to attend to the tasks of the hospital, between August and October 1936 the militiamen killed eleven of them.

At the beginning of 1937, the hospital was managed by the Socorro Rojo Internacional, under the medical direction of José Álvarez. Despite the changes produced by the war situation, the hospital continued to care for children. It is worth highlighting the great importance of paediatric surgery, especially aimed at correcting the major deformities and fractures produced by osteo-articular tuberculosis. With capacity for one hundred children, the health centre also attended to poor patients in the Maritime Villages on an outpatient basis. Likewise, the People’s Sanatorium welcomed part of the children evacuated from the San Rafael Asylum in Madrid, so it had to increase its healthcare capacity. This was accompanied by problems of shortages and lack of personnel and material, a situation that was repeated in the nearby Sanatorio Marítimo Nacional, then transformed into the Sanatorio Helio-Marino “Pablo Iglesias”.

Location: Riu Tajo Street, 1