The hut

Dades bàsiques

1 hour and a half

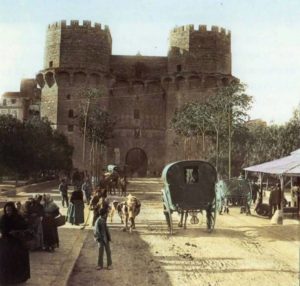

Serrans Bridge and Tower

Carrer de les Barques, corner Pascual i Genís or Guillem de Castro street

Again, following the movement of various characters from the Blasquist novel from Alboraia to the city, a route is proposed that starts from the towers of Serranos, then flows to the Plaza de la Virgen and Miguelete, and enters the Central Market area. From there there are two options on the itinerary: access to the Velluters neighborhood, with stops at the Colegio Mayor de la Seda and the old General Hospital, or route to what was the Pescadors neighborhood.

Although the main core of the action The hut It takes place in the orchards of Alboraia, the characters move frequently to Valencia, so from their movements it is possible to trace the following itinerary through the city, which is completed with some spaces closely linked to the biography of Vicent Blasco Ibáñez.

The avalancha of laborious people heading to Valencia filled the bridges. Pepeta passed among the workers of the arrabales who arrived with the saquito of the hanging lunch of the cuello, stopped at the row of consumptions to take their shelter – a few coins that every day doubled in her soul – and went through the deserted streets.

When Pimentó’s wife went to Valencia every morning with her cow, La Rocha, to sell milk, she had to make an obligatory stop for consumption, a small house that was located in strategic places at the entrance to cities, for example, on the Puente de los Serranos and on the Puente del Mar. There, employees collected municipal taxes on goods traffic (for this reason, consumption was called in Spanish as FielatosBy Faithful or needle of the balance used in the weighing of the goods) and also proceeded to a sanitary control of the food that was introduced into the city (and therefore the Fielatos were also called sanitary stations).

And poor Batiste, with the thought occupied by so many misfortunes, barring in his imagination the sick child, the dead horse, the unhagged son and the daughter with his reconcentrated regret, arrived at the scrambles of the city and passed the bridge of Serranos.

In the novel, Batiste Borrull goes, from Alboraya, to Valencia after the death of his old horse Morruto. To do this, a bridge must be crossed whose name responds to the fact that it was the access route for people arriving in the city from the inland region of Los Serranos. The current one, built between 1518 and 1550 under the direction of the master builder Juan Bautista Corbera, came to replace a previous one that was destroyed by the flood of 1517. In this bridge, of ojival trace, the sculptor Joan Gilart collaborated with the images incorporated in two houses that were destroyed, in 1809, during the War of Independence, to prevent the French troops from establishing an attacking trench in the place.

But the bridge was not only a transit point for travelers and peasants like Batiste and Pepeta. It is also given at least two other uses, as stated in the novel:

In front of the eight towers that soaked over the trees his ojival arcades, his barbecues and the crown of his almenas, Batiste stopped.

Built between 1392 and 1398, the Serranos towers served as a defensive bulwark for one of the twelve gates guarding the old city wall. This crenellated construction has a square front part and the corners cut off on two sides. Its back is flat and rises on three floors with pointed arches. Given its majestic structure, it was given a commemorative use, as in the official entries of kings, although in 1586 it also played the role of a prison enclosure.

Just three hundred metres from Serranos, on Calle de las Blanqueries, is the Benlliure House Museum, whose owner was a great friend of Blasco Ibáñez and illustrated the 1929 edition of La barraca.

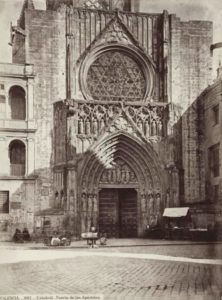

The Water Tribunal will meet at the door of the Apostles of the Cathedral of Valencia. […]

The door of the Apostoles, old, red, carcominated by the centuries, spreading its rogue beauties in the sunlight, formed a deep dignity of the old court: it was like a canopy of stone made to covet an institution of five centuries.

In the typhoon appeared the Virgin with six angels of stiff dawns and wings of small feather, furnished, with a lobster tupe and heavy slingshots, playing violas and flutes, caramillos and drums. Running through the three overlapping arches of the cover were three garlands of figurillas, angels, kings and saints, coveting themselves in draughts of four. On sturdy pedestales were exhibited the twelve apostles; but so disfigured, so maltrechos, that Jesus would not have known them: the red feet, the rotated noses, the cut hands; A row of figurones, who more than apostoles looked like patients escaped from a clinic painfully displaying their reports girls. At the end of the cover, you arrive, like a gigantic cobblestone covered flower, the colorful rosette that gave light to the church, and at the bottom, at the base of the columns adorned with coats of arms of Aragon, the stone was worn, the aristas and the follajes blurred by the frote of countless generations.

From the Torres de los Serranos, head along Carrer del Comte de Trénor and Carrer de Navellos until you reach Plaça de la Mare de Déu. There we can stop in front of the Apostles’ door of the cathedral, a unique backdrop for the Thursday meetings of the Water Court. Remember that the protagonist of La barraca was summoned by this “popular court”, when he was falsely accused by Pimentó of having watered his fields without respecting the established turn.

In stark contrast to the Romanesque door of the Palace or the Almoina, that of the Apostles shows a clear Gothic style. It was made at the beginning of the fourteenth century, but no documents have been found that prove the exact date or the authorship of the sculptural group, nor is it possible to specify the degree of intervention on the cover of the master builder of the cathedral, Nicolau d’Ancona (or d’Autun).

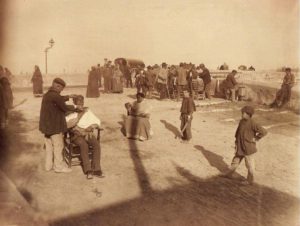

[Batiste] he had to visit the owners, the children of Don Salvador, and borrow them a piquillo to complete the amount that would cost him to buy a rock that would replace the Weevil. And as the toilet is the poor man’s luxury, he sat down on a stone bench, waiting for his hill to be lifted from two-week-old beards, punching and hard as punches, that blackened his face.

In the shade of the tall bananas worked the hairdressers of the huertana people, the barbers “facing the sun”. A pair of sparrow-seated armchairs and polished arms, an anafe in which the water stood, the dubious colored peacocks and honeyed navajes, which washed the hard complexion of the parishioners with creepy scratches, constituted the entire fortune of these open-air establishments.

Cerrile men who aspired to be mancebos in the barberries of the city made their first weapons there; And while they hid themselves infiring cuts or populating the heads with trasquilones and peladuras, the owner would talk to the parishioners seated on the bench of the promenade, or read aloud a newspaper in this auditorium, which with quijada in both hands listened impassively.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at the end of the Serranos bridge, on a stone ramp, “between two gardens”, in front of the towers, these barbers gathered with a humble clientele of which Blasco Ibáñez speaks.

The clock of the tower called the Miguelete signaled a little more than ten o’clock.

Like the characters in The Barrack, anyone attending the deliberations of the Water Court can easily notice the silhouette of the famous Micalet, an octagonal Gothic bell tower that was built between 1381 and 1429. The terrace is 51 metres high and ascends a spiral staircase with 207 steps.

There was a time when this building was part of a system of towers distributed along the Mediterranean coast and from which the imminent attack of Barbary pirates was warned. At night, with a bonfire (the smoke) it was indicated that there was no news, but with two bonfires a near danger was warned, while the enemy landing was proclaimed by throwing the bonfire from the top of the tower.

Behind the Basilica of the Virgin Mary, we can take an interesting trip to the past by visiting the Almoina Archaeological Museum or, already in the Plaza del Arqueobispo, the Crypt of the Prison of San Vicente and the Museum of the City, with pieces of enormous artistic value.

At dawn I [Pepeta] was back from the market. At three o’clock, he was carrying the cestones of vegetables cooked by Toni at the end of the previous night between refusals and vows against a picy life he has so much to work in.

On her first daily visit to the city, the place where Pimentó’s wife traveled would in no case be the current Central Market, inaugurated in 1928. Rather, the timestamps of fiction suggest that Pepeta would come to know the Mercat Nou or dels Pòrtics, inaugurated in 1839 and also located in a square with emblematic buildings of the city such as the Lonja and the church of Sant Joan del Mercat.

Over the centuries, this square has been an authentic nerve centre of Valencian life. There have been activities of very different kinds: chivalric tournaments, proclamations, rallies, bullfights (until 1743) and even public executions, to the point that there was a gallows installed in the middle of the square.

Silk factory

On the road [Roseta] Today she was like a tropel of fury, and only felt calm in the verse inside the factory, an old house near the Market, whose façade, frescoed in the eighteenth century, still preserved among deconchatures and grietas certain groups of pink piernas and tanning faces, remains of medallions and mythological paintings.

To help sustain the family economy, the Borrulls’ daughter goes to the city every day to work. Its displacement allows the route to be broken down into two alternative itineraries. The first, after surrounding the Central Market in search of Avinguda de l’Oest until it meets Carrer de l’Hospital, allows an approach to the Velluters neighbourhood, where silk artisans located their homes and workshops. In Valencia, this task reached an unusual boom, to the extent that it is ensured that in the second half of the eighteenth century there were more than three thousand looms that employed thousands of people.

In Carrer de l’Hospital you can visit the restored Museum and College of High Silk Art, a Gothic building from the fifteenth century inside which you can see beautiful frescoes and murals.

Old General Hospital

The daughters, one after another, were abandoning the families that had taken them away, moving to Valencia to earn their bread as maids; and the poor old woman, tired of bothering her illnesses, went to the Hospital, dying shortly afterwards [de Barret].

In the same street as the Hospital were the two entrances of what was originally the Hospital of the Fools, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, was the Hospital of the Fools, or of the Mad. Over time, the primitive asylum was expanded with various facilities (infirmary, pharmacy, church, etc.), until in 1885 the Faculty of Medicine was added. In this institution poor and needy people were helped, as Uncle Barret’s wife was in The Hut.

From Guillem de Castro street towards Plaça de Sant Agustí, we pass by where the old convent of Sant Agustí was, converted into a penal from the mid-nineteenth century to the first decade of the twentieth.

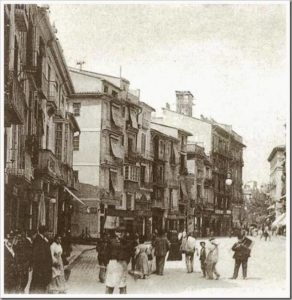

At o’clock, after serving all her customers, Pepeta walked near the Pescadores neighborhood.

As she also found in him, poor Huertana bravely indulged in the suicious streets, which seemed dead at that hour. Always as I entered I felt a certain disgust, an instinctive repugnance of delicate stomach […].

From the closed and silent houses came the halito of cheap, roaring and undisguised crapula – a smell of tanned and rotting meat, wine and sweat. Through the surrenders of the doors seemed to escape the crushing and brutal breathing of the crushing dream after a night of caresses of fiera and loving whims of drunk.

If Pepeta’s pilgrimage with La Rocha were to take place today, it could go down from the Central Market along Avinguda de Maria Cristina and Carrer de Sant Vicent to Plaça de l’Ajuntament, turning left to enter Carrer de les Barques, one of the roads that, next to Carrer de Lloria, Carrer de Pascual i Genís and Plaça de l’Ajuntament marked the boundaries of the old neighbourhood of Fishermen. It was an area where squids and people who made a living from fishing were installed, since there they enjoyed better living conditions than around the sea and, in addition, they could easily access Ruzafa, connected through its channels with the Albufera. In this neighborhood the boats were built that would later sail the waters; However, the atmosphere of quiet industriousness was replaced by a very different one when taverns, cafes and brothels proliferated in the place. It is precisely the atmosphere of corruption that so frightens Pepeta and that also alarmed the authorities, since scandals, fights and crimes were frequent.

At number 14 Joan d’Austria street, Blasco Ibáñez set up his home and the editorial office of the newspaper El Pueblo in 1894, so he knew the Pescadors neighbourhood very well.