Among oranges

Dades bàsiques

Between 1 hour and a half and 2 hours

Train Station

Alameda

Following what is narrated in the novel Entre naranjos, a route is drawn where the spaces through which the Alcirian protagonist of the story passed during his brief stay in the city before embarking on an amorous escape with the beautiful opera singer Leonora. Specifically, starting from the corner of Lauria street and Plaza del Ayuntamiento, we continue to the place where the disappeared Café de España was. Through Calle de las Barques you can reach the Teatro Principal, and from there to the Hotel Inglés (formerly of Rome), reporting on Plaza de Villarrasa and the Palace of the Marquis of Dosaigües. Afterwards, you enter the Literary University from Carrer de la Nau, and then go to the Parterre, then cross the Puente del Real bridge until it ends at the Alameda.

While the story told in Among oranges It takes place, fundamentally, in a rural environment that decisively conditions the love adventures of the protagonists and serves the author to denounce the ways of caciquism and local politics, the displacement of the characters to Valencia allows an interesting itinerary to materialize.

[Rafael] I had arrived on the first train in the morning, without any equipment, like a schoolboy escaping with only the post.

The starting point of our itinerary is located in the same place that the main characters of the novel would arrive from Alzira to enter the streets of the city. The train in which Rafael was traveling did not stop at what is now known as Estación del Norte, since it was inaugurated on August 8, 1917. The old railway station was located on the grounds of the now disappeared convent of Sant Francesc, in the square of the same name (today the Town Hall). For this reason, at the time it was also designated as Sant Francesc station. Approximately, it was located where the buildings of the Equitativa and Telefónica stand today.

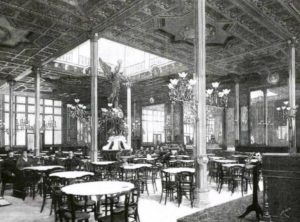

The old man led him to the Café de España, his favorite retreat. He had the table at the foot of the four watches that sustains the Angel of Fame in the center of the great square hall, with its huge mirrors of fantastic perspectives and its gilds darkened by the human and twilight that desciate through the high interior like an immense crypt.

Those who arrived at the Nord or Sant Francesc station could find, walking two or three minutes towards the cathedral, the place mentioned in the novel and which Blasco Ibáñez himself frequented with some regularity. El Café de España was an establishment where the novelist shared a gathering, rested from his hustle and bustle as editor of El Correo de Valencia and director of La Bandera Federal or wrote letters of passionate sentimentality to his girlfriend Maria.

The Café de España was located in Baixada de Sant Francesc, in Plaça de Caixers, and we would currently find it at number 9 of Plaza del Ayuntamiento. In the same place where the Valentino school had been, the owner of the café, a rich Aragonese, used the artistic gifts of Antoni Cortina to embellish a recreational place in which there was also a billiards room and an Arab room conceived as a replica of the courtyard of Ambassadors of the Granada Alhambra. Figures such as the carver Juan Estellés and the sculptor Josep Aixa collaborated in the ornamentation of the Café de España.

In the Plaza del Ayuntamiento, in the Town Hall building, the Municipal Historical Museum houses authentic relics of the city’s past, such as the Penón de la Conquesta, the sword of King Jaume I or the Royal Catalan flag.

[El doctor Moreno] He went to Valencia in winter to listen to the operas that praised the newspapers.

Going back a few meters in the Plaza del Ayuntamiento, we continue along Carrer de les Barques until we reach the Teatre Principal. Although in 1770 the architect Filippo Fontana was commissioned to draw up plans for a building in Italian style, the start of work took several years, and even after Cristòfol Salas made some modifications to the initial project in 1804, construction was interrupted by the French War. It was in July 1832 that the theatre grounds could be inaugurated.

Like Leonora’s father, Dr. Moreno, Blasco Ibáñez was passionate about opera and when circumstances allowed he used to attend the premieres that took place in the Principal. He would go with friends or even take his children to evening performances, an option that was considered unfair by some. Before becoming a father, it seems that the novelist had an affair with the Russian soprano Nadina Bulichov, who arrived in Valencia to open the opera season in the Principal at the beginning of November 1891. Possibly the character of Bulichev served as a model for the creation of Leonora from Among Oranges.

[Leonora y Rafael] They had just had breakfast among the suitcases and boxes, which occupied a large part of Leonora’s room in the Hotel in Rome. […]

The old hotel, with its large, high-tech rooms, its corridors in discreet penumbra and its conventual calm, seemed to him a place of delight, a pleasant retreat, in which he considered himself free from the murmurings and struggles that had oppressed him like a hellish circle. Besides, I heard that exotic wind there that seems to dine at the ports and the great railway stations. Everything spoke to him of the escape, of the uncertain and delicious concealment in that country so warmly described by Leonora, from the macaroni of the lunch and the chianti in a packed and ventruded house, to the defective and musical Spanish of the hotel dueños, fleshy men with huge mustaches reminiscent of the traditional musachos of the house of Savoy.

Leonora had summoned her there, in the artists’ favourite refuge, which, isolated from circulation, occupies a whole side of a solitary, signal and quiet square, with no noise than the screams of rental cocktails and the kicks of horses.

When Leonora and Raphael decided to flee Alzira thinking of fully enjoying their passion in a European country, they stayed at the Hotel de Roma before embarking on their great journey. This route runs to the hostel, which takes us from the Teatre Principal, following Carrer del Poeta Querol, until we reach the corner of Carrer del Marqués de Dosaigües and Carrer de la Cultura. There stands the Hotel Inglés, which in the late nineteenth century was Hotel de Roma and was formerly the old Gothic palace of the Duke and Duchess of Cardona.

In the novel, from the rooms of this building Leonora had a magnificent perspective to other spaces that are well known or that have already disappeared.

[Leonora] he found in it a memory of the squares of Florence, surrounded by closed and imposing mansions, with their paving of fiery twigs by the sun, among which grass grows and that wake up from their moderation to the late step of a woman, a cure or a traveler, repeating their pisades when they are already far away.

What seemed to Leonora to Leonora was the Plaza de Vila-rasa, a space surrounded by the Palace of the Marquis of Dosaigües, the Hotel de Roma and the Palace of the Counts of Nieulant (demolished in the mid-twentieth century), and which over time had to be opened to give better access to Calle de la Paz.

The young man [Rafael] was rushing around. He wanted to return as soon as possible, and quickly passed through the cloud of cocktails that offered him his services in front of the large palace of Dos Aguas, closed, silent, sleeping like the two giants that guard his cover, developing under the golden rain of the sun the sumptuous and graceful rococo style.

I looked out at the old farmhouses in the square, an angle of the Dos Aguas Palace, with their jasper stucco tables among the molds on the balconies.

The third scene that captivates Leonora’s gaze is the palace of the Marquis of Dosaigües, a construction whose current appearance is far from that of the old Gothic-style ancestral home of the Rabassa de Perellós (Marquis of Dosaigües), built in the fifteenth century. Three hundred years later, in the 1740s, the building underwent a comprehensive reform and the rococo style was applied to elements such as the ornaments that decorate the main door, made in alabaster by Ignasi Vergara based on the design of Hipòlit Rovira. After a new remodeling in the mid-nineteenth century, already in 1954 the monument was enabled as the National Museum of Ceramics and Sumptuary Arts. Inside it houses the magnificent collection of ceramics donated by Manuel González Martí, and dazzles visitors with luxurious eighteenth-century floats, as well as colorful eighteenth-century rooms, including the Chinese Room, the Porcelain Room or the Ballroom.

Ramón spent a few years in Valencia, without being able to jump beyond the prolegomena of Law, for the damned reason that classes were in the morning and he had to approach dawn, the time when the reverbs that focused their light on the green table went out. In addition, he had in his room of the guesthouse a magnificent shotgun, a gift from his father, and the nostalgia of the huertos made him spend many afternoons in the shooting of Palomo, where he was better known than in the University.

The surpluses and prizes of the school of Alcira were still in Valencia, and in addition Don Ramón and his wife were buried by the periods of the triumphs reached by their son in the “Juventud jurídico-escolar”, a night meeting in a classroom of the University, where the future lawyers were used to talk discussing topics as original as whether «the French Revolution had been good or bad» or «Socialism compared to Christianity».

Ramón Brull and his son Rafael studied Law at the University of Valencia with different advantages. In fiction they could be in the same classrooms where Blasco Ibáñez would also pass. The novelist had begun a licentiate of Civil and Canon Law in 1882, and obtained his degree in November 1888. For him it was a time when he was already beginning to publish his first stories and was signified by its vindictive character; For example, he organized a student strike in late 1884 in favor of academic freedom.

To reach the old University or Estudi General building, crossing Carrer del Poeta Querol we enter the Carrer dels Llibrers and, skirting the Plaça del Col·legi del Patriarca, we arrive at Carrer de la Nau. It was home to one of the oldest universities in Spain, since, founded in 1499, the Estudio General was inaugurated in October 1502. Its students were or officiated as teachers of the stature of the philosopher Lluís Vives, the botanist Cavanilles or humanists and scholars such as Honorat Joan i Maians. But the history of the building was also marked by very dramatic episodes. During the Napoleonic siege of the city, in 1812, there was a fire from which only the auditorium and the chapel were saved, and it was from 1840 that the reconstruction works of the university enclosure began.

Blasco Ibanez strove to make republican casinos a fundamental element in the organization of his political party. Precisely, in the Center of Republican Fusion of the Booksellers would materialize his project of the Popular University, exhibited in El Pueblo, on January 11, 1903.

Cabizbajo, terrified by the image of that scene after his eight, Raphael didn’t know where they were going. He was soon surprised by a perfume of flowers. They walked through a garden, and as they lifted their heads the arrogant figure of the conqueror of Valencia shone in the sun on his nervous war horse.

The character of Don Andrés has arrived in Valencia to convince Rafael Brull not to leave with his beloved Leonora: this would be a great discredit for the family. While the novel’s protagonist is confused by this plot, their walk through the city leads them to the Parterre. In our itinerary we will access these gardens, built around 1850, by the street of La Nau.

The Parterre occupies the centre of the square of Alfonso the Magnanimous and yet the figure standing on the high pedestal is that of King James I the Conqueror. It is an equestrian statue, modeled in the style of historicist romanticism, in which the attitude of the monarch guiding his army attracts the attention of the novelesque character and all those who contemplate it. After all, this was the intention with which the project of sculpting the image was promoted: to commemorate the sixth centenary of the death of the king, in 1276. Despite this, the realization of the sculpture, after being entrusted to Agapit Vallmitjana, took several years due to lack of economic resources to pay for it. Placed in its place in July 1891, five cannons and a howitzer that were in the castle of Peñíscola were melted in its elaboration.

Pasaban un puente. Downstairs, in the cautious dry, stood out the red and blue bellows of a group of soldiers and sounded the double of the drums like the humble of an enormous colmen.

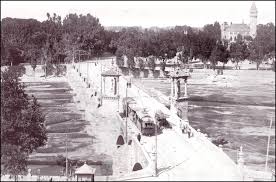

Continuing their arbitrary walk, Rafael and Don Andrés left the Parterre gardens behind and, turning along Calle de la Paz (formerly Peris i Valero), crossed the Plaza de Tetuán until they came across the Puente del Real.

This viaduct must have been one of the exits from the walled enclosure of the city. For this reason, it was formerly also called the Temple Bridge due to its proximity to the tower and gate of the same name (previously of Bab-el-Shadchar, where the church and the Temple Palace are currently located). However, the name del Real was perpetuated to connect the city with the palace of the same name.

The stone bridge we know today was completed at an accelerated pace, in 1598, after the ancients made of wood and other materials had not been able to resist the onslaught of successive floods or, as happened in 1528, the weight of the large number of people who came to receive King Charles I caused its solitude.

The one of the Real has ten arches and is adorned with two mansions with the sculptures of San Vicente Ferrer and San Vicente Mártir, made at the beginning of the seventeenth century by Vicent Leonart Esteve and which were replaced by identical ones as they were severely damaged during the Civil War. Likewise, in 1801 a neoclassical style Puerta del Real was built, demolished six decades later together with the walls, and of which the current Puerta del Mar is a replica.

In our walk through the Plaza de Tetuán we pass by the Museum of the Palace of Cervelló, residence of illustrious people during the nineteenth century and which houses within its walls the Municipal Historical Archive.

They were under the trees of the Alameda. The carriages walk along forming a huge wheel in the center of the promenade, the harriers of the fishermen’s horses and lampposts shining with the reflection of the sun, seeing through the windows the sombreros of the ladies and the white laces of the children.

The end of Rafael and Don Andrés’ journey ends at the Alameda, a setting that, as indicated in the novel, was to the liking of the Valencian bourgeoisie and nobility to show off their position by walking in colorful “carriages”. But the Alameda is also a space that immediately refers to a disappeared Valencia. In its origins it was known as El Prat, transformed in 1677 into a promenade with three rows of poplars, and what was the way to reach the Royal Palace from the sea had been embellished with new improvements at the end of the seventeenth century. Beyond the reforms that have been carried out over the centuries, up to that of the architect Javier Goerlich in 1932, it is interesting to emphasize that the attraction of this area located on the left bank of the Turia revolved around the Royal Palace.

This building, demolished in 1810, was in the eleventh century a place of recreation or rahal of Abd al-Aziz. But not only monarchs of the Valencian taifa stayed there. With the successive extensions and reconstructions resided the kings of the Aragonese crown, the viceroys or even it was an enclosure where at the end of the fifteenth century the Inquisition had its headquarters (reaching its age of splendor during the reign of Alfonso the Magnanimous). In this same century, following the medieval fashion recognizable in various European courts, a collection of exotic animals had gathered in the gardens surrounding the palace (gardens of the Royal or Viveros).

To round off the route, a visit to the Museum of Natural Sciences is of great interest, located in the incomparable setting of Vivers.